TRACE:

Traditional Arts and Crafts of Europe

HUNGARY

Corn Husk Weaving

Corn husk weaving dates back to the 17th century, when corn became a common crop in Hungary. Farmers sought to make use of every part of the plant, and they discovered that the husk could be fashioned into durable, useful objects. Over time, the craft became a winter activity, with families gathering to weave and make household items or sell their creations at the market. In the past, corn husks were used in many practical ways beyond weaving. They were stuffed into mattresses as a softer alternative to straw, used to sweep out ovens, tied around bottles or barrels for sealing, and even twisted into ropes for hanging clothes or tying up vineyards. Organized education in corn husk weaving began in Hungary in the 1920s and 1930s, with women and girls in several villages learning this skill. Corn husk items like bags, mats, and slippers became popular during this time. Collecting corn husks is a seasonal task, best done during the corn harvest from late September to early November, and care must be taken to avoid mold and damage to the material. Properly dried husks can be stored for years, ready to be transformed into intricate figures or practical items. Craftsmen who continue to work with corn husk today often showcase their work at fairs and festivals, where items like woven bags, baskets, mats, and even figurines can be found. The resurgence of interest in natural materials has made corn husk products popular once again, appreciated for their durability, eco-friendliness, and aesthetic appeal. Today, as part of the growing interest in eco-friendly and sustainable materials, corn husk products like baskets, bags, and coasters are experiencing a revival. Corn husk weaving is a craft that connects past traditions with modern sensibilities, preserving an ancient art form while adapting it for today’s world. It takes skill, patience, and a love for handmade beauty to bring these simple materials to life in forms that continue to be cherished across generations. The essence of corn husk weaving involves twisting strips of corn husk to form objects. One of the unique tools used in this craft is a hooked needle, which helps pull the twisted strands into place. Mastering the twisting technique is key, and while it's relatively easy to learn, achieving smooth and even weaving requires significant practice. Patience is crucial, as the weaving process is slow - making a single bag or basket can take up to five days. One of the biggest challenges today is sourcing the raw material. Modern harvesting machines shred the corn husks, and the traditional small farms where corn was hand-harvested have disappeared, along with the practice of small-scale animal husbandry. To preserve the craft, some artisans have resorted to growing their own corn, as one weaver explains, dedicating part of her land to grow corn specifically for husk weaving.

Handcraft artist: Gelencsér Julianna.

Workshop: Kozák Téri Közösségi Ház

Embroidery

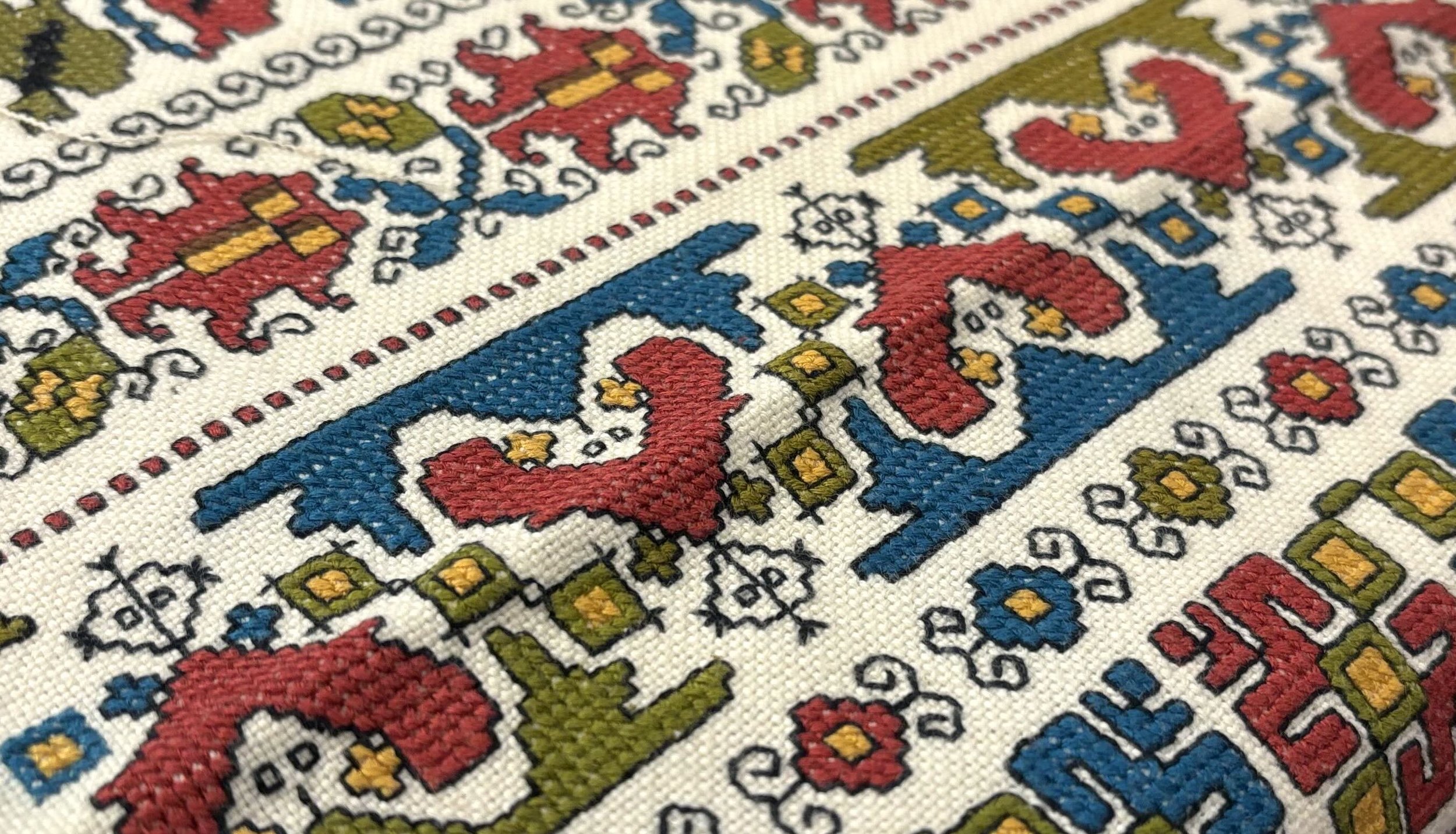

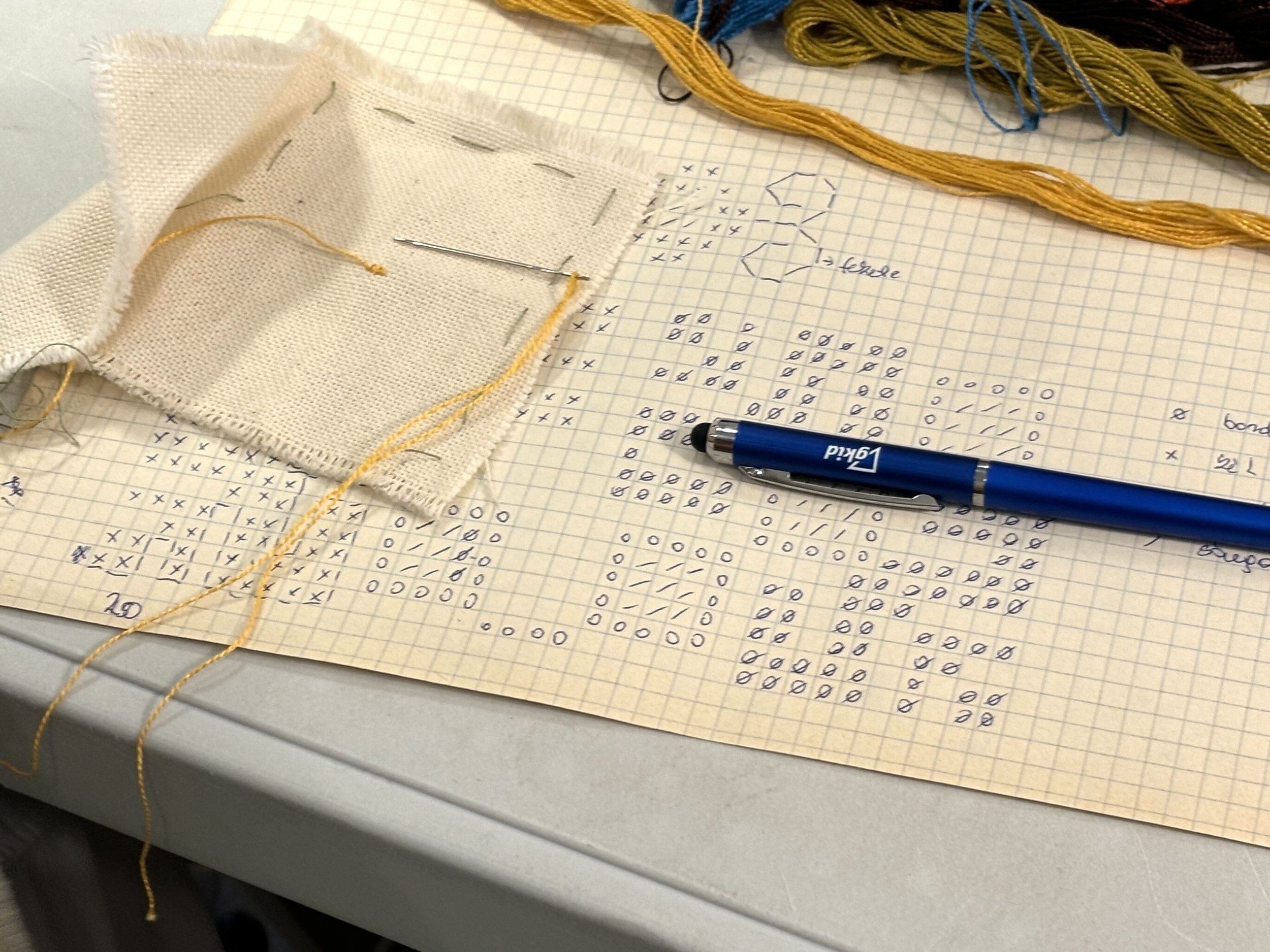

Embroidery is a technique used to decorate materials like fabric, leather, or other textiles by stitching with a needle and thread. Unlike weaving or lace-making, where threads form the fabric itself, embroidery is added to a pre-existing material. This craft can also involve metallic threads, though this is rare. Often referred to as "sewing" in rural areas, embroidery can be combined with other decorative methods like appliqué or weaving. Embroidery has a long history, with evidence of basic techniques dating back to the Neolithic period. While some theories suggest embroidery may have evolved from weaving, this is not proven. In Hungarian folk art, embroidery holds a particularly important place. From the early 19th century, the demand for decorative items grew, particularly those made by women of the household, like embroidered linens and clothing, which became a key part of the home’s decoration. While embroidery became central to the decoration of homes and clothing in many regions, it was less important in others. In places where embroidery was highly valued, it even shaped the interior design of rooms and the traditional clothing worn by both men and women. However, this also increased the workload of women, as embroidery was a time-consuming craft. Hungarian folk embroidery can be categorized based on the materials used. Linens were often embroidered with cotton, linen, or hemp threads by women, who sometimes became specialists in the craft. Leather or wool embroidery was mainly done by men, particularly tailors and furriers, who applied it to garments like coats and vests. Embroidery adorned a wide variety of items, from everyday clothes like aprons, shirts, and caps, to household textiles like pillowcases, sheets, and tablecloths. It was also used for special occasions, such as wedding gifts or funerals, where embroidered items were displayed as symbols of respect and celebration. Various techniques were used in embroidery, including flat stitches, cross-stitches, and chain stitches. The type of stitch used depended on whether the pattern was geometric, requiring precise counting of threads, or freehand, where the design was sketched directly onto the fabric. Embroidery played a key role in Hungarian cultural traditions. For example, during weddings or funerals, embroidered textiles were displayed prominently. The embroidery’s placement was strategic, with designs often focused on the edges of linens or the most visible parts of garments.

Workshop leader: Illés Károlyné

Location: Kozák Téri Közösségi Ház

Traditional Basket Weaving

Basket weaving and willow bending are among the oldest known crafts, practiced for centuries across various cultures, including Hungary. The craft utilizes primarily wild basket willow and grey willow (commonly known as rabbit willow). It spread rapidly among people engaged in agriculture and animal husbandry. Farmers wove baskets for harvesting, grain storage, and grape harvesting, while livestock keepers crafted pens, fences, feed baskets, and bee hives from wicker. During wartime, even coffins were made from this versatile material. Everyday objects like coal and wood baskets, and outdoor brooms were also crafted from willow. Basket weaving is a highly detailed and labor-intensive craft, involving several stages before the basket takes shape. The willow branches, once harvested, are boiled for eight hours, peeled, sorted, and dried. The prepared material can then be stored for up to 10 years, maintaining its quality. The tools used for basket weaving include willow branches, knives, pruning shears, various types of awls, pliers, and hammers. In the 19th century, this rural, self-sustaining craft evolved into a cottage industry. Unpeeled or "green" willow was used for rougher woven products, with these craftsmen known as "kaskötők," or makers of coarse baskets. They created items needed for farming and daily life, such as fences and chicken coops. The more refined craft of weaving boiled and peeled willow into household items required greater skill and became the domain of specialized basket weavers, known as "kosárfonók." Their work included finer, detailed products for everyday use, such as fruit baskets and furniture. The craft's roots extend back to ancient times, with evidence suggesting that basket weaving predates pottery. Archaeological finds show clay-covered baskets that were fired, leaving the imprints of the weaving on the pottery, proving its ancient origins. It is said that the Hungarians who settled in the Carpathian Basin already knew the craft, which developed alongside their farming practices. By the 18th and 19th centuries, industrialized basket weaving spread from France and Germany throughout Europe, bringing the familiar, more structured forms of today’s baskets. Hungary’s rich tradition of basket weaving is particularly strong in regions like Békés, Mezőberény, Körösladány, Elek, and Tiszaalpár, areas abundant with willow trees due to the proximity of rivers like the Körös and Tisza. The fishermen of these regions were likely the first willow benders, using the material to craft fishing tools and storage containers. Over time, the craft became deeply integrated into agricultural life, with woven products meeting a wide range of practical needs. Willow bending required minimal, yet specialized tools. Craftsmen often made their own equipment from available resources, including seating supports, frames, sorting boards, and various cutting tools such as carving and trimming knives. The shaping of the wicker without splintering required precision tools like hammers and pounders. The techniques of basket weaving were typically passed down from father to son, though it was also possible for dedicated individuals to master the craft through time and effort. Beyond baskets, the weaving technique was used for fencing, barn partitions, and wagon structures, demonstrating the craft's versatility and utility in rural life. Round-bottomed baskets and bee hives were among the more complex items produced, while peeled, finer willow was used for elegant, hand-woven baskets and even furniture. The enduring appeal of Hungarian basket weaving lies in its simplicity, practicality, and connection to the land. By working with the natural materials around them, Hungarian craftsmen created essential, durable goods that have stood the test of time.

Workshop leader: Kovács Zoltán.

Location: Kozák Téri Közösségi Ház.

Hungarian Gingerbread

Gingerbread making is one of the most interesting crafts, with a very long history. The first gingerbread is thought to have been a paste made from honey, cereal flour and water, which was stolen from wild bees, dried on a hot stone and later baked in an oven. In the Egyptian pyramids, not only honey but also leftover honey dough was found. The Greeks sacrificed figures made of honey dough to their gods. The Romans, who were also gourmets, were also known for their honey cakes, honey plates and honey thallies, which were made in the form of clay moulds depicting mythological scenes and portraits of their rulers. In Hungary, during the reign of the Árpád-House kings, beeswax figures, honey drinks and honey cakes were made in monasteries with their own apiaries and later in the settlements around the monasteries. From the 15th century onwards, the moulds for making gingerbread were carved from wood (hardwood, most often pear or walnut) by the masters themselves or their skilled assistants, but also by specialists who made moulds for gingerbread workshops. For centuries, gingerbread was synonymous with the monochrome delicacy patterned with wooden moulds. (The technique involves pressing the honey dough into the mould with negative chiselling, so that the pattern is transferred to the dough and, after turning it out of the mould, appears as a positive on the surface of the dough. After drying and resting, the patterned dough is then baked out.)

The real heyday of mould carving was the 17th-18th centuries. While the earlier carvings were mostly religious, with biblical scenes, depictions of saints, rulers and historical figures, later on, everyday themes also appeared on the mosaics, and the public at fairs and fairs could choose from a wide range of designs, including folk heroes: fairy-tale heroes, outlaws, hussars, animal figures, folk art, lucky charms (e.g. chimney sweep, clown), etc. The design transferred from the carved mould to the gingerbread often had a symbolic meaning, the gingerbread conveyed a message, which could be a message of love through the hearts, but also a message of good luck, wishing children, good health, a long and happy marriage, life, healing, fertility or a funny, humorous hint, e.g. The shapes have also been used to introduce technical innovations (balloon, automobile), but also to mark special and significant events such as the arrival of the first giraffe in a European zoo. From the middle of the 19th century, besides the plain gingerbreads made with truncated trees, there appeared the more colourful, ornate, fancy gingerbreads decorated with mirrors, paper pictures, inscriptions, coloured flowers. In our country, these are collectively known as 'farewell gingerbread'. Typical examples are the red, mirrored heart or the colourful, paper-headed figure of a knight. The honey in the dough was replaced by sugar syrup, and the decoration was provided by icing instead of elaborately carved patterns. The more ornate, ornate gingerbread men overshadowed the flamboyant gingerbread men. The carved shapes (with the exception of Debrecen, our only gingerbread centre) were hung on walls, in attics and later in museum collections.

In the last century, with the development of the confectionery industry, gingerbread-making as a craft has been in sharp decline, and today there are hardly any small-scale traditional gingerbread workshops in the country. Yet it can be said that gingerbread making, and all its forms, is enjoying a renaissance in Hungary today, with skilled craftsmen making and selling delicious and beautiful traditional and modern gingerbread based on the former gingerbread pattern in their homes, in workshops, at workshops, at events of folk art associations, festivals and workshops. Among the many different techniques, the carved woodcarved gingerbread is very popular in our country, and based on the rich museum collection of woodcarvings (thousands of pieces), our woodcarvers recreate old patterns, create new ones and sell their carvings at folk art fairs. In our workshops, the percussion technique is easy to learn and quick to learn with proven recipes and properly carved patterns, and the slow, beautiful process results in a honey-rich, long-lasting, delicious confection using only natural ingredients. The sweet gift of a craft technique that is thousands of years old, full of beauty and mystery.

Text and photos: Seregély Mirtill.

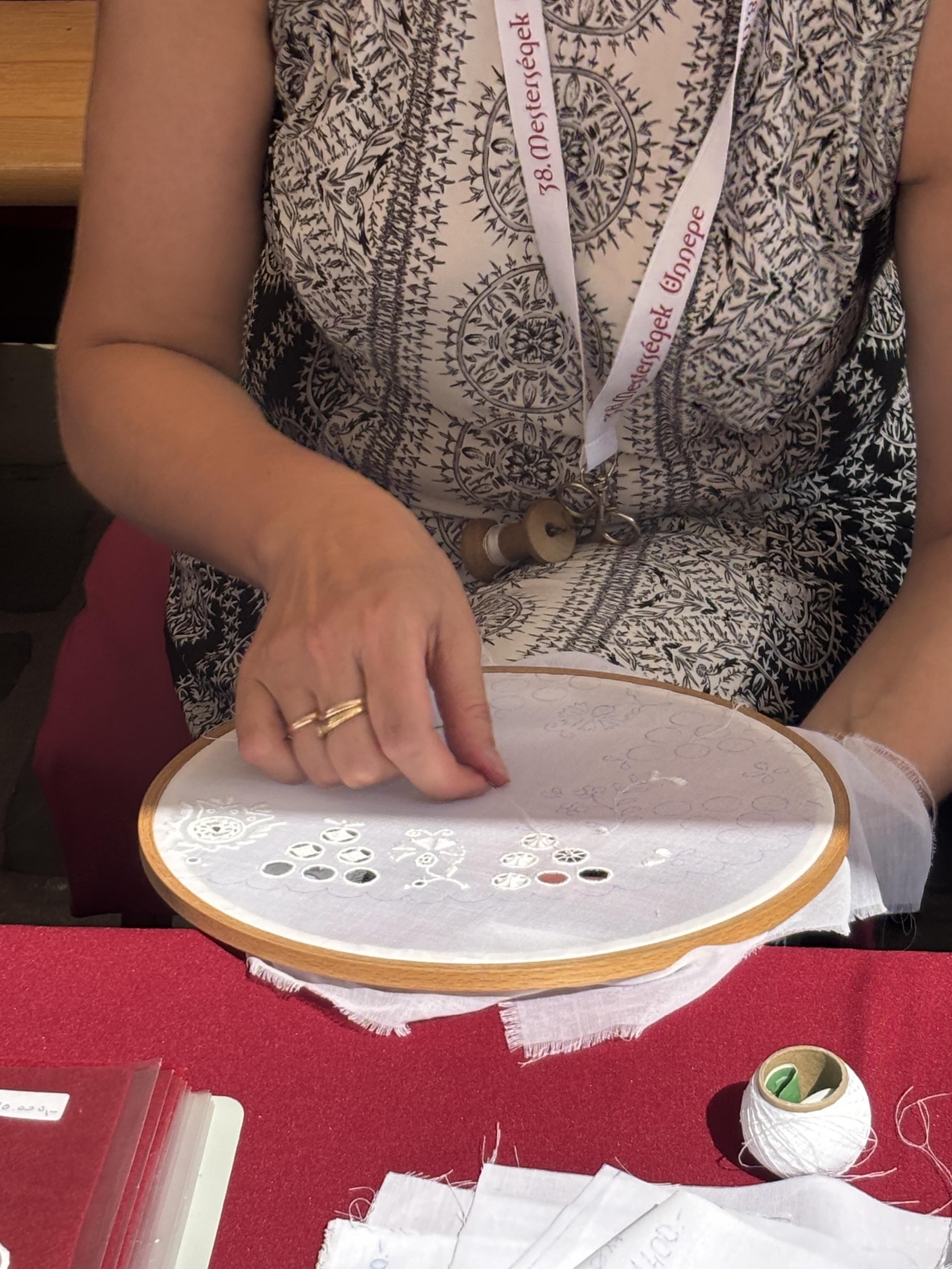

Höveji Lace

Höveji lace, a delicate and intricate form of Hungarian embroidery, originates from the small village of Hövej in northwest Hungary. Renowned for its exquisite detail and fine craftsmanship, Höveji lace represents a unique facet of Hungary's rich cultural heritage. This handmade lacework is celebrated for its exceptional beauty and artistic value, combining functionality with artistic expression. The tradition of Höveji lace dates back to the early 19th century. Initially created as a practical embroidery for household linens and garments, it gradually evolved into a highly decorative art form. Local women developed this unique style to embellish dowries, church textiles, and festive attire, making it an integral part of regional cultural identity. Over generations, the craft has been passed down, preserving its authentic techniques and patterns. Höveji lace is characterized by its intricate needlework and the use of fine white cotton thread on linen fabric. The process begins with carefully drawn patterns on the fabric, often inspired by natural motifs like flowers, leaves, and geometric shapes. The embroidery employs a combination of openwork (cutting and pulling threads from the fabric) and needle-lace stitching, creating a delicate, three-dimensional effect. One hallmark of Höveji lace is its extraordinary precision, achieved through meticulous, time-consuming handiwork. Common stitches include the "Granny's eye" and "Twisted bar", which contribute to its distinctive look. Traditionally, Höveji lace was used to embellish: tablecloths and napkins, curtains and bedspreads, church textiles, clothing. In 2013, Höveji lace was included in the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Hungary, highlighting its cultural importance. Efforts to preserve and promote this tradition include workshops, exhibitions, and craft fairs, ensuring that new generations of artisans continue to practice and innovate this remarkable art form. Höveji lace is more than just a decorative textile; it is a testament to the creativity, skill, and cultural heritage of Hungary. Its delicate beauty and rich history make it a cherished symbol of the country’s artistic traditions, captivating admirers around the world.

Artists: Höveji Csipke Egyesület

Location: Mesterségek Ünnepe, Budapest

Archive footages: Pócza Margit, lace-artist

Wood and Bone Carving

Carving can be done from various materials, but the most common is wood, which has been used to create carved objects for centuries. In addition to wood, materials like horn and bone are also used, which provide unique textures and allow for distinct shapes and patterns. Various tools, such as chisels and knives, are used for carving, enabling shepherds and craftsmen to create everyday objects. In Felsősegesd, a village in Somogy County, the works of Mihály Tóth, a master shepherd carver, exemplify traditional carving art. One of the most striking carving traditions can be found in Transylvania and the region between the Danube and Tisza rivers, where geometric patterns, often crafted using a compass, are the dominant motifs in carved objects. These patterns appear on ceiling beams, furniture, and even tools. In Kalotaszeg, it was common for young men to carve the base of a spinning wheel for their beloved. If they lacked the skill, they would commission a master craftsman. Geometric ornamentation was widespread across Europe, but it survived most robustly in the wood-rich region of Transylvania, where both Hungarians and Romanians embraced the craft. Shepherds would often spend their time carving while tending to their livestock. Wooden items such as walking sticks, drinking vessels, matchboxes, and children's toys were common. Horn, particularly cattle horn, was used to create drinking horns and whetstone holders. The unique texture of horn allowed for carved items with distinct shapes, often adorned with geometric and floral patterns. Carving styles and techniques varied by region. In Transylvania, geometric elements were dominant, while in other areas like Transdanubia, the Highlands (North Hungary), and the Great Hungarian Plain (Alföld), different styles evolved. For example, in Transdanubia, colorful flowers, trees, animals, and scenes from shepherd life often appeared, whereas in the Great Hungarian Plain, horn carving was a deeply rooted tradition. The figures of outlaws and bandits were particularly popular in shepherd art, appearing not only in folklore but also on carved objects. The central motifs of shepherd carvings often included animals, flowers, and scenes from daily pastoral life, reflecting the environment and experiences of their creators. Horn and bone were also important materials for carving. In the Great Hungarian Plain, shepherds and hunters demonstrated exceptional artistic skill when working with horn, crafting items such as powder flasks and drinking horns. The carved decorations on cattle horns often featured rich floral designs and geometric elements, influenced by the carving traditions of neighboring peoples, such as the Slovaks and Rusyns. Bone carving was also widespread. Shepherds crafted small bone beads and ornaments, often decorated with geometric patterns. These designs evolved over centuries and in some cases were discovered in burial sites from the migration period. The art of carving is rich and diverse, reflecting the folk culture and lifestyle of various regions. The different techniques and motifs make each carved object unique, preserving the legacy of Hungarian folk art to this day.

Artist: Keresztes Levente

Location: Mesterségek Ünnepe, Budapest

Archive pictures: Faragvány Díszítések (1963), Diafilm Múzeum.